Cultivating a Healthy Codebase: Beyond Code That Just Works

Newsletter about software engineering, team management, team building, books and lots of notes I take after reading/studying (mine or yours)… :D

In software engineering, there's an inconvenient truth every experienced developer knows: the difference between a project that accelerates over time and one that grinds to a halt lies not in the brilliance of its initial code, but in its ability to evolve.

Let's be honest. We've all felt that chill down our spine when tasked with modifying a critical module. That fear that a small change could trigger a cascade of unpredictable side effects. This feeling is a symptom. The diagnosis? A hostile codebase.

A hostile codebase is expensive. It drains productivity, frustrates developers, and turns innovation into a risk management exercise. The goal of this article is to dive deep into the principles and practices that transform a software liability into a strategic asset: a healthy, friendly, and evolvable codebase.

The "Why": Architecture as an Enabler of Agility

The agility to implement, test, and change behaviors doesn't happen by chance. It is a direct consequence of deliberate architectural decisions. The ultimate goal of a good architecture is to minimize the cost of change over the software's lifecycle.

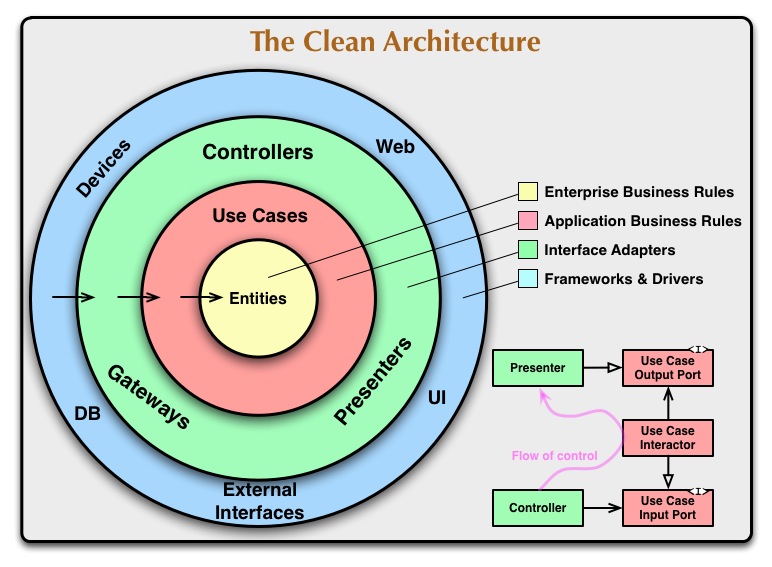

The Dependency Rule and Clean Architecture

Robert C. Martin, in his seminal book "Clean Architecture," provides us with the most powerful guideline: The Dependency Rule.

High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions. Source code dependencies should always point inwards, towards higher-level policies.

In practical terms, this means that your business logic (the rules that generate value for the company) should know nothing about the database you use, the web framework you've chosen, or the user interface you render.

(Source: The Clean Coder Blog)

(Source: The Clean Coder Blog)

Why is this so transformative?

- Inherent Testability: If your business logic doesn't depend on a real database or web server, you can test it in milliseconds, using test doubles (mocks/stubs) in place of dependencies. Testing fast is the foundation for changing fast.

- Interchangeability: Imagine this scenario: the marketing team requests a new feature to log customer anniversary events, which can have varied data structures. To implement this efficiently, the engineering team concludes that the best approach is to migrate the profile storage to PostgreSQL to leverage the powerful

jsonbdata type.- In a coupled architecture, this would be a nightmare. The business logic would be entangled with calls to the old database, requiring a dangerous, high-risk rewrite across multiple parts of the system.

- In a clean architecture, the business logic (the "heart of the system") doesn't know which database is used. It only communicates with an abstraction, an interface like

IProfileRepository. Implementing this new feature becomes a surgical task: we create a newPostgresProfileRepositoryclass that implements the existing interface and "plug" it into the system. The core of the software remains untouched, stable, and oblivious to this major infrastructure change. The technical decision serves the business, without the business becoming a hostage to the technology.

- Focus: Developers working on business logic can focus on the business problem ("what are the rules for an anniversary event?") without being distracted by the complexities of the infrastructure.

The SOLID Principles at the Micro Level

If Clean Architecture is the urban plan for our software city, the SOLID principles are the building codes for each structure. They help us implement the Dependency Rule at the class and module level.

- (S) Single Responsibility Principle: A class should have one, and only one, reason to change. A

TaxCalculatorclass should not be responsible for saving the result to the database. This isolates the impact of changes. - (O) Open/Closed Principle: Software should be open for extension but closed for modification. Instead of changing an existing class to add a new payment type, you create a new implementation of a

PaymentMethodinterface. This prevents breaking what already works. - (L) Liskov Substitution Principle: Subtypes must be substitutable for their base types without altering the correctness of the program. This ensures that the abstraction you've created is reliable and that polymorphism works as expected.

- (I) Interface Segregation Principle: No client should be forced to depend on methods it does not use. Creating small, focused interfaces (

Payable,Refundable) is better than a monolithicFinancialManagerinterface. - (D) Dependency Inversion Principle: This is the heart of the Dependency Rule at the code level. Instead of a

UserServicedirectly instantiating aPostgresRepository, it depends on anIUserRepositoryinterface. The concrete implementation (Postgres, MongoDB, etc.) is "injected" from the outside.

The "How": Disciplined Practices for Maintaining Health

Having a good architectural design is not enough. We need daily disciplines to build and maintain quality.

Test-Driven Development (TDD) is Not About Testing

Contrary to its name, the primary benefit of TDD is not the resulting test suite (though that's an excellent side effect). TDD is a design discipline.

The Red-Green-Refactor cycle forces us to:

- Red (Write a failing test): Think first about the desired interface and behavior. What do I want this code to do? How will I use it? This forces the creation of clean, focused APIs.

- Green (Write the simplest code to pass the test): Focus on making one thing work, avoiding over-engineering.

- Refactor (Improve the code's design): With the safety of the test suite, we can now improve the internal structure of the code. This is where we apply SOLID principles, remove duplication, and increase clarity, knowing we haven't broken anything.

TDD is what makes refactoring safe and, therefore, feasible to practice continuously.

Refactoring: The Continuous Hygiene of Code

Michael Feathers, in "Working Effectively with Legacy Code," brilliantly defines legacy code: legacy code is simply code without tests. Why? Because without tests, we cannot refactor it safely.

Refactoring should not be a "project" scheduled for the next quarter. It should be a continuous practice, like washing the dishes after cooking. It is the "Boy Scout Rule" applied to software:

"Always leave the campground cleaner than you found it."

When fixing a bug or adding a small feature, take the opportunity to make a small improvement: rename a variable to be clearer, extract a complex method into smaller ones, break a dependency. This compounding effect of improvements is what prevents the codebase from deteriorating.

The "Culture": The Human Factor and Technical Leadership

None of the practices above survive in a vacuum. They need to be sustained by an engineering culture that values quality, collaboration, and, crucially, technical leadership.

The Staff Engineer's Perspective: The Architect and Guardian of Codebase Health

The existence of a healthy codebase is not an accident but the result of deliberate and persistent technical leadership. In her book "The Staff Engineer's Path," Tanya Reilly deconstructs the senior engineer (Staff+) role, showing that their greatest contribution comes not from the volume of code they write, but from their ability to act as a force multiplier for the entire team. In the context of a codebase, this multiplication takes very concrete and profound forms.

Let's abandon the simplistic view that the Staff Engineer just "writes the hardest code." Their real job is to ensure that the easy code to write is also the right, sustainable code.

1. Seeing the Forest, Not Just the Trees: "Big-Picture Thinking"

One of the fundamental distinctions Reilly points out is the shift from local optimizations to a systemic view.

- A Senior Engineer sees a performance problem (an N+1 query, for example), fixes it efficiently, and moves on. The local problem is solved.

- A Staff Engineer sees the same problem and asks, "Why did this happen? Why didn't our ORM, our code review tools, or our tests warn us about this? This is the third time this month we've fixed an N+1 issue. Does our data access layer promote this type of error? Do we need a new abstraction or a specific linter to prevent this entire class of bugs in the future?"

This is the application of "Big-Picture Thinking." The Staff Engineer isn't just fixing a leak; they are analyzing the entire plumbing system to understand why the pipes keep bursting. For the codebase, this translates to:

- Influencing Architecture: Advocating for architectural changes that eliminate entire classes of problems, rather than applying countless "band-aids."

- Defining Technical Strategy: Helping to draw a map of where the codebase needs to evolve in the next 1-2 years to support business goals, identifying the most strategic technical debt to pay down now.

2. The "Glue Work": The Invisible Work That Upholds Quality

Reilly gives special attention to "Glue Work"—the often invisible and unglamorous work that connects people, systems, and processes. In a codebase, this "glue work" is the immune system that keeps it healthy. The Staff Engineer is the primary agent of this work, acting as the "guardian of technical quality":

- Establishing and Automating Standards: It's not enough to say "write tests." The Staff Engineer ensures the CI/CD pipeline is fast, reliable, and blocks code without adequate coverage. They define linting and formatting rules that are applied automatically, making the quality standard the path of least resistance.

- Improving the Developer Experience (DX): A build that takes 15 minutes? A development environment that takes a day to set up? This is friction that encourages shortcuts and frustrates the team. The Staff Engineer invests time in optimizing these tools, knowing that a fast feedback loop is essential for safe refactoring and experimentation.

- Writing the Important Documentation: Not the documentation that repeats what the code already says, but the documentation that explains the why. Documenting an architectural decision, the reasons for choosing one technology over another, or the trade-offs of a complex module. This is the knowledge that prevents future teams from repeating past mistakes.

3. "You're a Role Model Now": Leading by Example

The Staff Engineer leads by example. Their code is not just functional; it is a teaching tool.

- Exemplary Pull Requests: Their PRs are clear, well-described, with tests that not only prove functionality but also document behavior. They demonstrate the patterns the team should follow.

- Code Reviews That Raise the Bar: In a code review, they go beyond "missing semicolon." They ask strategic questions: "Is this new dependency aligned with our long-term vision? Have we considered how this approach will scale? Is there a simpler way to solve this that will be easier for the next developer to maintain?" They use the CR as a mentoring opportunity, raising the technical level of the entire team.

In short, a Staff Engineer's contribution to a friendly and evolvable codebase is less about their individual output and more about creating a socio-technical system where quality is a natural outcome. They don't just build good "buildings" (features); they design the "city" (architecture), write the "zoning laws" (standards), and ensure the "transportation routes" (pipelines and DX) are efficient for all the other builders. They transform codebase health from a heroic individual effort into a collective, manageable responsibility.

Conclusion: An Investment with an Exponential Return

Building and maintaining a friendly codebase is not a luxury; it's an economic necessity for any tech company that wants to move quickly and sustainably.

It is an effort that combines an architecture focused on separation of concerns, daily practices of TDD and refactoring, and a culture of collaboration led by engineers who think systemically. The initial cost of adopting these disciplines is paid back multiple times over by increased development velocity, a decrease in critical bugs, and, perhaps most importantly, a happier and more engaged engineering team.

A healthy codebase is a living organism. It breathes, grows, and adapts. And our job as engineers is to be its best caregivers.

We talked about staff responsibility, but this extends to all team members (especially leaders). It's important that each team member takes responsibility and works together to maintain healthy code.

Further Reading

- Martin, Robert C. Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship. Prentice Hall, 2008.

- Martin, Robert C. Clean Architecture: A Craftsman's Guide to Software Structure and Design. Prentice Hall, 2017.

- Feathers, Michael C. Working Effectively with Legacy Code. Prentice Hall, 2004.

- Reilly, Tanya. The Staff Engineer's Path: A Guide for Individual Contributors Navigating Growth and Change. O'Reilly Media, 2022.

- Fowler, Martin. Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code (2nd Edition). Addison-Wesley, 2018.